EAVESDROP! Psycho Bitches—Orli Auslander, Julie Holland and Elisa Albert in Conversation

In celebration of Orli Auslander’s outstanding new book I Feel Bad earlier this year, her friends, co-conspirators, and fans Elisa Albert (After Birth, The Book of Dahlia) and Julie Holland, MD (Moody Bitches) gathered at Housing Works Bookstore Café in SoHo for a free-range conversation about motherhood, shame, estrogen, cannabis, catharsis, and more.

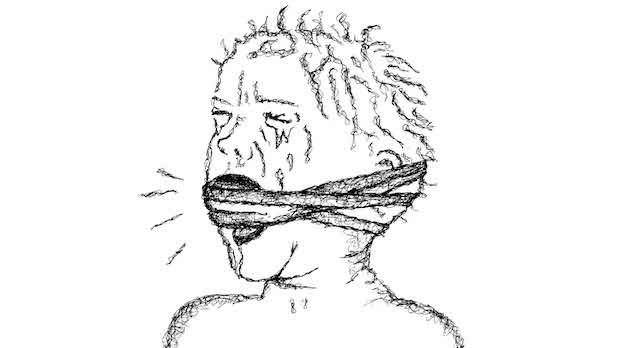

I Feel Bad is a brave reclamation of the shadow self, an instant classic that transcends age, class, race, and gender, and will resonate with anyone who has ever heard a troubling inner monologue. Here’s an abridged version of their wide-ranging conversation.

Julie: We’re all dressed like we’re going to a shiva.

Elisa: We did not plan it this way.

Orli [squinting into the spotlights]: Well these lights aren’t at all intimidating, are they.

J: Maybe we’re all in mourning for…

O: Mother’s Day.

J: I was thinking for the planet, but Mother’s Day works.

E: You know, some guy at the supermarket wished me a Happy Mother’s Day yesterday (I was shopping, alone, for groceries) and I said, uh, thanks, but like, if this is annoying to me, and I’m relatively happy, with a pretty nice intact family, this must be just fucking horrible for like everybody else.

O: For the less fortunate?

E: Yes. And he said ‘Have a nice day!”

O: And you didn’t tell him to fuck off?

E: I did not. I thought it, though.

O: So how was your mother’s day? Did you spend it with your mother?

J: I called my mother. And I read a novel, which I really enjoyed.

E: The one about the Manson family?

O: Perfect for Mother’s Day.

E: I had my mother with me, and I had a little muscle right here, kind of at the base of my skull, maybe an occiput? And it was very angry, that little muscle, the whole day.

O: Because of your mother?

E: I don’t know, I’m just saying. The body knows.

J: The body knows!

O: I think Mother’s Day is the day you should speak to your mother. That’s THE day. Of the year. Seriously.

E: Imagine what a happy conversation that would be! ‘Oh my god, how are you!?’

O: ‘So nice to speak to you!’ No, I did not speak to my mother on Mother’s Day.

J: Do you want to talk about that, Orli? How does that make you feel?

O: Um, how much time do we have left in this session, Doc?

J: I’m sorry, our time is up.

E: Why don’t we just say: “Bad”

O: I spoke to her the day before Mother’s day. I have carte blanche because mother’s day in America is a different day. In England it’s in March. So I can ignore both. I can feel bad twice a year, instead of just the once.

J: Not according to your book! Which I read it in one sitting. Emailed a blurb back that day.

O: Thank you for that.

J: I so strongly identified. I’m not suggesting it’s only for perimenopausal women, but it definitely spoke to me.

O: Do you think men will get anything out of the whole perimenopausal thing?

J: I think it’d be smart for men to educate themselves and arm themselves with information about this particular stretch of a woman’s life, because we are a little bit more, I think, emotional and reactive than we are at other times…

E: What the FUCK is that supposed to mean?

J: So there’s this thing called estrogen, and when you have less of it, when it starts to wane in your forties and fifties, you get a little bit less accommodating, a little bit less like dithering and like ‘I don’t know, whatever you want, honey’.

O: I can’t differentiate between the pre- and the post-. I feel like I’ve been lacking estrogen since I was like, eight.

J: Estrogen is the hormone of accommodation. It allows you to be sort of resilient and pliable and a little bit like ‘okay, yeah, that’s fine, I can handle it, that’s fine, whatever you want.’ So when estrogen starts to wane, like with PMS or with perimenopause, it’s more like ‘no, that’s not okay, why would I do that, do it yourself, that’s not my job.’ But the important thing about estrogen is that it very much waxes and wanes.

O: Depending on how often you smoke pot.

J: Depending on your menstrual cycle. There are times in your menstrual cycle when you’re more likely to do people favors and other times when you’re more likely to be like ‘fuck you, do it yourself.’

E: So, basically, Orli, you started to go through menopause like the moment you started menstruating.

O: Pretty much. I don’t think there was any gap where I was feeling like yeah, you know, this feels alright.

E: Maybe that’s coming!

O: WHEN? When I have my uterus ripped out?

E: I will testify that, having had your book on my coffee table for a while, I’ve witnessed many, many different kinds of people kind of surreptitiously absorbed in it. They pick it up like oh, interesting, there’s a naked female form on the cover, I’ll take a look. They start to flip through more and more intently, kind of looking around to see if anyone is watching. Then an hour has gone by and you hear them laughing uproariously.

J: I really did actually laugh to the point where I was crying. I was with my friend ice-skating when she broke her wrist and I grabbed your book to take to the emergency room, because I knew it would distract her and make her laugh while she was sitting in pain. Laughter truly is the best medicine.

O: It helps.

E: Have there been any clinical trials around laughter?

J: What would be the placebo?

E: Oh-ho, I know some people.

J: Orli, you do reveal a lot of truth about yourself in this book, but you also end up revealing a lot about your sons and your husband. I’m very curious about how that went over.

O: Um… [locates her husband in the crowd] Would you like to answer that, love? My soon-to-be ex-husband. I felt like I didn’t reveal so much. I tried to stay away from the kids as much as possible, and, you know, when they’re in therapy in a few years they’ll probably have a different response…

J: I think about my kids in therapy a lot, too.

O: It’s just a matter of time.

J: I’m like, ‘Molly, don’t forget to tell your therapist that I’m not just critical but I’m controlling, too. Don’t forget. I’m controlling, too, got it?’

O: She’s not in therapy yet? That’s a good sign.

J: I bill parents all the time for my patients. That’s karma. That’s the way it works.

E: Like, literally? You send the bill to the parents?

J: Directly to the parents.

E: No comment.

O: So let me ask you a question. The guilt thing. This is not the question, but does everyone expect you to have the answers, because you’re the doctor?

J: I dissuade people from that pretty early. I focus on the biology and the psychopharmacology and prescribe medications and what’s working, what’s not working. Most of my patients have therapists. When they start getting into sort of heavy interpersonal stuff I will be like ‘this sounds like something for your therapist.’

O: Okay, so the reason I ask that is because the thing that’s come up quite a lot with the book is whether it’s ‘a female thing’. Guilt. And shame. Which—obviously not. But it’s maybe more of a female thing? Even though I know that my husband and my kids unfortunately, because I fucked them up already, they feel guilt intensely.

J: It may be a generational thing. It may be shifting. Traditionally women are sort of the martyrs, we take on things and don’t complain until it gets completely overwhelming. I had shame just growing up because I knew my parents wanted boys, and they had three girls.

O: Disappointment in the vagina.

J: I think girls are less second-class citizens in this generation than they were in previous generations.

E: I think it’s just, like, dressed up nicer. Dressed up different. [To Julie] I read a review of your book that seemed to embody exactly how and why everything is exactly the same as it ever was. In some women’s mag. The writer was so fucking offended by your suggestion that like we might have some like biological factors that make us different and we might want to, like, “respect” those factors…? The book was sort of panned for being ‘anti-feminist’. The idea that women and men are different, that our brains are different, and our hormones are different, and of course we are going to sometimes behave differently… if you admit that women have particular hormonal factors, or emotional responses, then you can’t be a feminist.

E: Because maybe we’re not serving ourselves super well by blunting those realities all the fucking time so that we can force ourselves to function as though we are not the organisms we actually are!?

O: Right, we’re supposed to ignore the whole… uterus… thing.

E: Otherwise you can’t be President!

O: Ix-nay on the agina-vay!

J: I always talk about the suppression of the Yin, the feminine energy. For thousands of years men have been taught don’t cry, don’t be acting like a little girl, little pussy. The worst thing for a man to be is emotionally expressive. But now women are getting that same message. Now we’re being told to man up, and we’re taking medications to dull our emotional receptivity. And I think that’s terrible, because there’s already a Yang imbalance in our culture. It’s so male-dominant. Think about guns and missiles and rape and war: it’s all very penetrative energy. What we need is more Yin energy. More receptive energy. More ‘let’s wait and see and try to synthesize.’ The fact that Yin has been suppressed for so long in men and now it’s being suppressed in women, I think is absolutely hazardous. A real problem with our culture.

O: Can’t be good.

E: I like the term ‘penetrative energy’.

J: You like that? I could say it again.

O: But you didn’t answer my question! Female guilt!

J: I don’t know.

O: Women get blamed a lot more, just going back to the Bible, even. So we’re bound to feel guilty more.

E: Well if you cook while on your period you do poison the food a little.

J: If you want to talk about the Bible, women are vilified as bringing everything down, I mean everyone has to leave the garden of Eden because of a woman.

E: I was supposed to be a boy. My parents were sure of it. At the moment of my birth my father went “He’s a girl!?” I don’t have the guilt as much. Just the shame. [to Orli] I like how you said you try to leave your kids out of it but right behind you is [a poster-sized panel from I Feel Bad:] “Sometimes I want to gag my baby.”

O: That’s about me, not the baby!

J: There are a lot of confessions in this book. Did you exorcize some of your guilt and shame in the process?

O: I would love to say that I did. But, uh…

E: But did you have a moment of grace? When you sent off the manuscript?

O: ‘Bout fifteen minutes.

E: And what about when women come up to you and say ‘Thank you, I love your book, thank you for saying all the things I wish I could say…’

O: I feel like there’s something terribly wrong with them, obviously.

J: It’s very liberating to see that you have some of the same struggles that I do.

O: That is cathartic. My oldest doesn’t want to look at the book at all. He says he hates the idea of me feeling bad. I say don’t worry about it! It’s just my way of laughing at it!

E: Don’t you think kids know exactly who their parents are, anyway?

J: There’s one particular panel about washing the dildos that I could certainly understand not wanting the kids to see.

O: Right, so I asked my eldest whether he had seen that one, and he goes ‘well, I knew you had sex, I mean I never wanted to imagine it, but…’ And I said ‘was there anything else that was a surprise?’ And he was like ‘no.’

J: There is some allusion to pot smoking in the book…

O: It’s not just an allusion.

J: Is that something you hide from the kids?

O: Yes. I mean, that’s what I was waiting for him to say he’d found out about that when he read the book. But we live in Woodstock, for god’s sake. So the conversation has come up before.

E: Julie, do your kids know you smoke pot?

J: That’s a really good question. I will say yes. But we still don’t really talk about it.

E: Ok. And how does that make you feel?

J: I’ve actually been lecturing about this. Outing yourself. The thing that will push drug policy forward the fastest is if people really do out ourselves. Say ‘I’m a soccer mom and I vote and I smoke pot.’ It’s this Harvey Milk idea. You have to out yourself and say ‘I want my rights.’ As pot smokers we should really out ourselves so we can move policy. It’s still not easy to talk to your own kids about, though. But I live in a town that’s pretty small and churchy, so maybe if I lived in Woodstock it’d be easier. Or Manhattan.

E: Well, if you lived in Manhattan your kids would be whoring for heroin.

O: No, these days they’d just be selling real estate…

E: …For heroin. Orli, can you talk about the idea of permission? As in: giving yourself permission? As a writer and artist? Because I think your work gives other people permission, you know? To actually say, oh, wait, it’s funny and real to be fucked up, and I don’t have to pretend I’m not, ‘cause everyone is!’

O: I wish I could say it comes from giving myself permission. Initially I it came from desperation. I can remember the first couple drawings I did, when I was in the throes of post-partum, and just feeling really angry and needing some sort of outlet. I started to keep lists, because I noticed myself feeling bad from the second I woke up in the morning. Like ‘oh, pressing the snooze button again, you fucking lazy cow.’ It was just like literally from the moment you wake up to the moment you go to sleep: every voice was this chastising, angry, middle-eastern mother. (I wonder whose voice that was!) And the more I wrote down every instance of feeling bad, the more I realized fuck, this is constant, I should probably address it a bit more. It was good to do a drawing and be able to laugh at it.

J: That’s so healthy.

O: Sometimes I used to imagine my own mother sitting around laughing at me, at my mothering skills, or my kid just going crazy, doing things I might have done when I was a kid, and I thought, okay well, I’ll draw that. It hasn’t stopped me from feeling bad a million times a day, but I can laugh at it now, and go okay! It’s that voice again.

E: And now you can monetize it.

O: That’s very cathartic.

J: Kaching therapy.

O: Helps pay for the Prozac.

J: Do you guys want to talk about meds? I’m here for a consult.

E: No, but can you talk about the effects of marijuana on different parts of the menstrual cycle? Like: marijuana in the follicular phase vs marijuana in the ovulatory phase?

J: There’s a really long history of using cannabis as a medicine for women, and there was actually a patented medicine, I’m blanking on the name, something like Cramp-Away. Back in the 1800s when cannabis was actually prescribed for cramps and childbirth and nausea in pregnancy.

E: So was Opium, to be fair.

O: No, Opium’s just for kids.

J: Cannabis is useful for women especially in the PMS phase of their cycles. When your estrogen is lower and you have a shorter fuse, you’re less resilient.

O: I think you have to save the cannabis for when you’re older. I’m not joking.

E: Older than who!?

O: Around, I would say… 30. Don’t smoke cannabis til you’re 30. Save it for when you really need it.

J: There really is a lot of evidence to support what you’re saying. As long as the brain is developing, into the early 20s, it’s best to hold off.

O: Even without fucking up your brain.

E: Has there ever been a culture throughout all of human history that did not self- medicate in some way?

O: I would never believe it.

J: Mormons. No alcohol, no opiates.

O: Hang on a minute, what about God!?

E: The ultimate opiate.

J: Even animals will take drugs to alter their consciousness. There’s a great book about it, published by Inner Traditions. There are examples of birds that eat berries to get them drunk, cats and catnip, reindeer would eat mushrooms and then drink their urine and get high off that…

[The lovely Rachel Fershleiser raises her hand]: Is there anything you’re inspired by? Music or art or…?

O: Some art.

E: [laughing] “Some”.

O: Nothing contemporary. Fucked up stuff. Kiki Smith. Edward Gorey. Joe Coleman. Some of the more twisted things, I find very inspiring. Van Gogh. Not so twisted, but his life was very inspiring. Just to know that, you know, I haven’t cut my ear off yet.

J: Always an option. But who would you send it to?

O: My mum, who else?

E: Happy mother’s day! Do your boys know you menstruate?

O: Oh yeah. Their nickname for me is HOM. Hormonal Mom, fused together. So,

yeah, they know.

J: Do mind me asking how old you are?

O: 48.

J: They ain’t seen nothin’ yet. It’s gonna get worse before it gets better.

O: That’s when we’re going to build a little cabin outside.

J: “The Artist’s Studio”

O: The red tent.

J: I love the idea of a red tent.

E: It’s for us. You’re not supposed to practice yoga during menstruation and inevitably there are women who are like ‘that’s ridiculous! I’ll practice 24/7, thank you very much!’ And it’s like no, no, no: chill! Take a nap! You’re off the hook! It’s not a punishment! You don’t have to clean or produce or make food or tend to the needs of others for a few days! Congrats. It’s a gift. It’s for your benefit. Go! Use it. Enjoy!

J: You’re allowed to be off-duty or incapacitated. If that were more formalized in our culture, it’s possible people would use less drugs to make themselves incapacitated on a regular basis. If they knew that a couple days out of the month they could just veg out.

E: [to Julie] Your book helped me with that a lot. It articulated these things in a way I hadn’t seen before, and it gave me permission! A few days a month, I’m like, out, love y’all, kisses, see you on the other side.

O: It didn’t do that for me at all.

E: Maybe you read it during the wrong phase of your cycle.

J: The idea of the red tent is also to decrease shame and guilt around this experience and make it something sort of sacred and dare I say celebrated. At least you make some space for it.

O: I like that idea but it quickly turns into: You have to be in the red tent, bitch. Very quickly gets out of hand.

J: Well orthodoxy is pretty fucked up, safe to say.

O: Orthodox anything.

J: It breeds shame, for sure. Big component of shame and guilt in most religions. I think you doing this book is so brave.

O: Brave? Desperate?

[Shalom Auslander, from the audience]: While your shrink was reading the book, did he charge you for that time?