Immaculate Assumptions: Food Babies I Have Carried

The first time it happened, I was fifteen. When I was called into the guidance counselor’s office, I was wearing cutoff jean shorts and a billowy tank top (“fat clothes” in my mind), and I weighed 124 pounds.

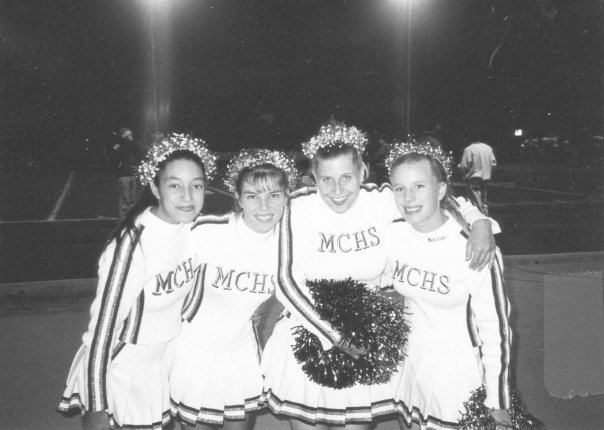

Back in the fall, I’d whittled myself down to 107. Friends, strangers, and my drill team coach praised my weight loss. I started shedding hair on my head and sprouting it on my lower back. I felt like a beautiful, sexless, vertical line.

What can I tell you about Manhattan Beach, California? A local nonprofit sponsored the after-school sports programs, including drill team. A tall, athletic woman gave us weekly lectures about health: how to pump up our pecs to make our boobs look big, how to make fat-free food choices like bagels and Red Vines.

Cool Manhattan Beach girls got summer jobs at Diane’s, a bikini shop a block from the pier.

I knew two girls who repeated eighth grade, despite being A students, so they’d have a better chance of making varsity volleyball their freshman year of high school.

The guidance counselor was also the girls’ volleyball coach. She was perpetually tan except for a reverse-tattoo of her sunglasses. Everyone said she was a dyke, but I liked her anyway, because she’d given me permission to drop AP European history.

A couple of my teachers were concerned about me, she said, and I cringed at the scrutiny it implied. Maybe it was just puberty, she said—girls developed at different rates, and perhaps I was just a late bloomer—but could it be possible that I was pregnant?

I burst into shame-tears. I had just been called to the principal’s office for being fat. There was a guy I flirted with in English class, and I stayed awake at nights worrying maybe I was a dyke like Ms. Aldrich, but that was the extent of my sex life. If it was possible to be negative-pregnant, that was me.

*

I was pregnant for nine weeks in 2011. I was jacked up on IVF hormones and rituals that tapped the same part of my brain that had taken so easily to anorexia. The part that believed in biology as destiny and as currency. I was not wrong—biology is destiny and currency; it’s just not the only destiny, and we can remake our economic systems. Back then I thought I might still be able to win by the rules as they were written.

I never got my baby bump, but when I look at pictures of myself from that time, I see how full my face is. Probably from what I was injecting, not what I was creating. Does that still count as looking pregnant?

*

The second time it happened, I was leaving our monthly book club. I was 34 years old, wearing an empire-waist sundress, and I weighed 137 pounds. I was two months post-miscarriage, and it had taken every bone in my defective body to drag myself there that night, because my friends Jamie and Lee-Roy brought their six-month-old. Kohana was a beautiful baby, Kewpie-doll-faced with light brown curls. I hated pregnant women and new moms, but try as I might, I couldn’t hate babies.

My partner C.C. and I got into the elevator with Jamie and Lee-Roy and a couple we didn’t know. The woman fussed over Kohana and I counted the floors: 11, 10, 9….. Then she turned to me: “And how about you? When are you due?”

When I talked to my therapist about it later, he posited that the woman must have read some kind of maternal energy that was rolling off me. And while that reading could be too generous, I know how intense I was at that time. My energy could easily have filled an elevator like a suffocating perfume.

*

The third time, and the fourth and fifth and sixth, I was working at Homeboy Industries, a nonprofit that helped former gang members get back on their feet. Pregnancies were part of the fabric of daily life there, an antidote to the hopelessness of street warfare and the belief that you wouldn’t live past 25. My boss in the development department was in her late forties. One day a client looked at the photo of her children, ages twelve and ten, on the file cabinet and said, “Aw, are these your grandbabies?”

When C.C. and I adopted, a year into my employment at Homeboy, Dash was received with the same warmth and celebration and lack of judgment as any baby born to a fresh-out-of-the-camps teenager. He was kissed and cuddled and passed around.

Homies were not a subtle bunch, though. When I put on weight in the frenzied exhaustion of new motherhood, no one hesitated to ask if I had another one on the way.

On my way out the door one day, a bakery employee named Aracely put a hand on my arm and congratulated me.

When I told her I wasn’t pregnant, she said, “Are you sure?”

“I’m sure. I’m married to a woman. If I was pregnant, it would be a miracle.”

“You have to believe in miracles. My sister thought she couldn’t get pregnant, and then she did. Miracles happen.”

*

Then there was the man at McDonald’s who told Dash that soon he would have a younger sibling. There are, at this point, too many instances to count.

This isn’t a story about how rude people are, or even (just) about how women’s bodies are always subject to public scrutiny, although they are. Every time it happens, those truths hit me secondarily. My first feeling is one of shame and accountability. If I don’t want people to think I look pregnant, I should stop going around looking so pregnant. Shouldn’t I?

I’m wondering if you’re thinking, Well, if you’re eating at McDonald’s, no wonder you look pregnant.

Or maybe you weigh 325 pounds and are beautiful and proud and would like for me, a medium-sized person who is a little bit swaybacked and carries her weight in her stomach, to shut the fuck up.

Maybe you came of age later than I did, far from the beach, and my shame seems alien and sad. But it is mine, as much as my squishy midsection, as much as the child I didn’t birth.

*

A friend with stage IV breast cancer started an Instagram account called @dying4sex. She posts pictures of her thin body and reconstructed boobs in beautiful lingerie and overlays it with brutally honest text about the realities of life with a terminal diagnosis. Recently, she wrote that it’s hard for her to eat because she feels like she’s feeding the cancer; she knows it’s a problem, and she’s trying to see food as fuel. Her posts reveal that a sexy body can be dying, and a dying body can be sexy. (P.S. All bodies are dying.) And her posts let her call the shots when reality won’t. Like anorexia and binge-eating, Instagram is about control.

When I had cancer—a junior-varsity stage II—I weighed 120 pounds for reasons that had nothing to do with chemo. I didn’t want to feed the cancer. I wanted to call the shots. And I felt that if I had to lose such feminine markers as hair and boobs (which I mourned in that order), I could at least hold onto thinness, the only thing our culture might value more than hair and boobs.

I’ve been thinking about @dying4sex’s posts a lot; I can feel myself envying what I “shouldn’t,” and also what I am meant to. I can feel myself wanting to live in the purity of those posts. Her pale skin, her uncluttered bedroom.

My life is big right now, which is how I want it. But my stomach and thighs have grown with it, as I struggle to keep up with the demands of child and work and spouse and art. And the part of me that says fuck-it and binges on Oreos and eggnog is the part that thinks I “should” be eating like someone whose only job is to prevent a cancer recurrence. It’s not like all the antioxidants in the world can actually push the snowball of cancer back up the hill, but a girl can dream. I did and do.

*

The last time someone clocked me as pregnant—and surely it wasn’t the last time—Dash and I were at the library. He was playing an ancient Dora the Explorer game on the computer when I spotted Casey, a woman I’d met once before through mutual friends.

After we exchanged greetings, Casey said, “Oh, and I should say congratulations!”

I looked down at my body, wondering for a second if I was wearing a T-shirt with my organization’s logo, and she was congratulating me on something work-related. By now, I should have known better.

“I didn’t realize you were expecting,” she said.

Casey was a white woman in her forties, a mom and therapist with the kind of haircut I would definitely get if I made time to get my hair cut more than twice a year.

“Oh, I’m not, I just…I don’t know….the holidays?” I laughed weakly.

So begun the dance where she felt embarrassed and guilty, and I felt embarrassed and ashamed, and we both tried to no-big-deal our way out of it. Maybe because she was a therapist, the dynamics felt closer to the surface than in other exchanges. She knew that women are judged by their bodies, and she said it anyway, because for her, perhaps pregnancy wasn’t quite such a loaded thing.

The second time she apologized, I said, “No, don’t worry about it, it’s a body type.”

“It’s not just—” she stumbled. “Last time we talked, maybe you said something about planning to try for a second? Or is your partner pregnant? Was that it?”

“We are thinking about a second,” I said, “but we adopted, so that’s the rout we’d go this time too.”

I helped Dash navigate the Dora game, and Casey told me about her day sorting through the school district’s red tape to find kindergarten options for her son.

Casey said, “There are so many choices—public, charter, private.”

“We’ll definitely be going public.”

“Oh, then you should know about SAS. Do you know about SAS?”

“No, what’s that?”

“It’s this designation that certain public schools apply for to attract ‘gifted’ students from ‘engaged’ families.” Her air quotes showed she understood that these words were code for white and middle-class. “But all you need to do to get your child designated as gifted is get letters from his preschool teachers.”

I thought back to my recent conference at Dash’s preschool. His teacher had gone into detail about his subpar scissoring skills, but punctuated her assessment by saying, in her Brooklyn accent, “He’s a good boy.”

The idea of asking Dash’s teachers to write, on paper, that Dash was more intelligent than the other kids in his classroom was only slightly more appealing than the idea that they might say, “Nope, sorry, not until he learns to use those scissors better.”

Casey seemed to share my skepticism about these designations, but she figured it was a game worth playing if you wanted to game the Los Angeles Unified School District, whose schools were, themselves, trying to game LAUSD.

It would take incredible hubris, as the parent of a four-year-old, to grandstand about my commitment to a public school system I haven’t even entered. I’m not above strategizing in my kid’s favor. But I can say with some degree of confidence that trying to wedge Dash into a school that skews white and middle class won’t be my first stop. I’m not going to assume that children of color who live in poverty and the people who teach them have nothing to offer my child—a child of color whose parents are clinging to the middle class by a thread. Assumptions are what got us here.

The crack between Casey and I widened, even though I liked her.

As I suffer from the hazards that come with being a woman between 15 and 45 who has a belly, I benefit—daily and invisibly—from assumptions people make based on my skin and gender. I look like someone who won’t steal anything or stab anyone. A different man, at a different McDonald’s, once asked me to watch his daughter while he went to the restroom. I wondered if he knew how many times, in those years before becoming a parent, I’d entertained kidnapping fantasies.

Therapists talk about being “defended,” which is sort of like being defensive, but more internal. Starving yourself to ward off cancer. Putting on lipstick so no one will suspect you spent the morning crying. Sticking to a precise schedule so you don’t have to face your fear of chaos. Writing about your body issues so that you can reclaim the narrative from people who have opinions about it.

What if I let my body exist in the world undefended? I am a person who always looks a little pregnant. I am a person who would like to have better eating habits and lose 25 pounds and game the system I know I should be dismantling. Maybe I’ll do both. Maybe I’ll do neither. For now, I’m not defending any of it.